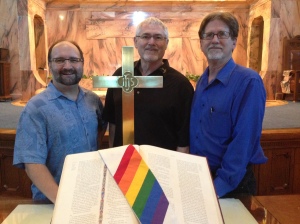

When I sat down recently with three Austin ministers — the Revs. Sid Hall, Larry Bethune and Jim Rigby — to discuss their experiences as early LGBT allies in the church, I was surprised to learn how much they struggled personally and spiritually. Why would that be surprising? Why didn’t I pick up on that when I covered them on the religion beat back in the day? You think you’re really digging deep sometimes as a reporter, that you’re getting the whole story. But, as I write in this Austin American-Statesman column, I didn’t take into account that these passionate activist clergy were also human. That they suffered from loneliness and self-doubt and fear.

The column is a narrow glimpse into these ministers’ experiences. I also wrote a longer piece that goes into more detail.

Prophets of Inclusion: Three Austin pastors and their struggles to promote LGBT equality

Not long ago, at a Methodist church, the Rev. Sid Hall found himself weeping quietly in his pew. It should have been a happy occasion. The church was celebrating LGBT inclusion, a cause for which Hall has spent the last few decades crusading.

But in that moment, the Trinity United Methodist pastor felt the full weight of the struggle — the loneliness and fear he experienced as an outspoken ally to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. He was viewed as a radical, a heretic. At times, he worried he would lose his job, his church.

“(I remembered) how scared I was, how alone I felt, how people walked on the other side of the hall at conferences to ignore me,” Hall said.

Fellow Austin ministers — the Revs. Larry Bethune of University Baptist Church and Jim Rigby of St. Andrew’s Presbyterian — are intimately familiar with those feelings. Like Hall, they risked their careers to preach and practice what they believed was a radical Gospel message of love and acceptance. Like Hall, they were ostracized by some of their spiritual brethren.

The three ministers rejoice in seeing more clergy take up the banner of equality and celebrate the Supreme Court’s decision that legalizes gay marriage. But they also remember the dark, anxious days marked by hate mail and charges of heresy.

Bethune sometimes wants to ask those who have more recently joined the cause: “Where have y’all been?”

The work is less lonely these days. While Hall’s denomination still bans same-sex marriage and gay ordination, many Methodist leaders are now calling for change. Rigby’s denomination, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), recently opened the door to gay marriage and clergy. And Bethune has inspired likeminded Baptists to embrace LGBT members.

Recently, in anticipation of the Supreme Court’s historic ruling, they gathered at University Baptist to reminisce about their individual awakenings on LGBT equality, the challenges they faced and the progress they’ve seen in both the church and state.

When a young associate pastor poked her head in, Bethune introduced his friends: “These guys are prophets of inclusion. They were leading the conversation and making trouble 25 years ago.”

The Rev. SID HALL, pastor, Trinity United Methodist Church:

Hall, who has a down-home Hoosier way about him, says he doesn’t think of himself as an activist as much as a “recovering placater,” always struggling to find the courage of his convictions.

Many years ago, he dreamed he was watching his own funeral.

“He didn’t have an enemy in the world,” said one of the mourners.

“That’s because he never stood up for anything,” said another.

The words chilled him.

In 1988, Hall was assigned to Trinity, a dying church in Hyde Park.

“It needs new life or a good funeral,” his district superintendent told him.

The young minister set out to fill the pews. He invited people from the neighborhood who seemed to appreciate his progressive approach to Christianity.

Trinity began to grow. Then a woman confided in Hall that she was gay and asked if she could come out to the church’s Bible study group. Hall discouraged her.

He’d been asked to leave his previous church for being too radical. He wasn’t sure he was ready for this. But he kept hearing that voice from the dream: “He never stood up for anything.”

Hall called the woman back and gave her his blessing.

In 1990, he presided over a lesbian wedding. In 1992 — despite the bishop’s attempts to prevent it — Trinity voted to become a reconciling congregation, meaning the church actively welcomed LGBT members. About 35 members left, taking hefty tithes with them.

At one point, Hall considered asking his mother for a loan to pay his salary. Instead, the church sold an antique Coke machine.

And so it went. Hall was committed to the struggle. He stopped conducting heterosexual weddings at Trinity. If gay people couldn’t be married in the church, then no one would be. He was arrested for protesting at national church conventions. Some of his fellow Methodists treated him as a pariah. Others offered support behind the scenes but didn’t take a public stand.

“The ones that create the most challenge for me are people who I know in their heart have views similar to mine,” he said, “but they’re not going to take the risk.”

He found comfort in his friendship with Bethune and Rigby.

“With these two guys, now I can be myself,” Hall said. “Now I can relax.”

The Rev. LARRY BETHUNE, pastor, University Baptist Church:

Bethune has a stately manner. White hair, trim goatee and a wise, unhurried way of speaking. He earned a master’s degree and PhD from Princeton Theological Seminary, where he became “cognitively aware” of his own biases.

He says he was “marinated in homophobia” — an expression borrowed from Episcopal Bishop Greg Rickel.

Confronting his prejudices in an Ivy League classroom was one thing. The real test for Bethune came when he began pastoring University Baptist 28 years ago.

He knew his congregation on the edge of the University of Texas campus included gay people, but no one spoke openly about it.

“Let it rise organically,” advised a pastor who had navigated the gay ordination issue at a different church.

So Bethune waited.

In 1993, Hans Venable, a gay man, was nominated to become a deacon. The congregation approved, and Bethune ordained him.

The church’s student minister at the time was outraged and alerted some of Austin’s most conservative pastors. The Austin Baptist Association called for a meeting.

It wasn’t the first time that University Baptist had stirred the pot. Members had voted for racial integration in the 1940s. The church had women in leadership. But a homosexual deacon was a step too far for many Baptists.

The association asked if Bethune was aware that Venable was gay. Bethune didn’t have to answer. One of the elderly members who attended the meeting said, “Yes, we knew. But we didn’t think it mattered.”

The church lost its fellowship with the local Baptist association and, later, the Baptist General Convention of Texas. And though most of the congregation stayed put, Bethune said the publicity prompted backlash.

“It’s a lonely experience to have a church in controversy,” Bethune said. “You’re trying to be pastoral in the midst of getting hate mail.”

But he drew on the strength of a congregation that had a long history of social justice.

“Without a prophetic church, I wouldn’t still be here,” Bethune said. “I get a lot of credit for what the church decided.”

The Rev. JIM RIGBY, pastor, St. Andrew’s Presbyterian Church:

Of the three, Rigby always struck me as the most intense, the biggest risk taker. There’s a sense of urgency when he speaks whether it’s from the pulpit or the steps of the Texas Capitol. With the Gospel in hand, he is constantly challenging the establishment and the privileged.

It’s hard to imagine, but when Rigby was growing up in Dallas, he believed the paramount virtue was “being nice.”

Years later, as a pastor, he witnessed police brutalizing protesters at a gay rights rally and immediately recognized his own homophobia — and the reason he had been so hesitant to ally himself with the LGBT movement.

“I was afraid people would think I was gay,” he said.

Niceness wasn’t such a noble virtue, he decided. Really, it just meant “wishy-washy.”

“There comes a day,” Rigby said, “when you have to cross a line.”

He quit wearing his clerical vestments in the 1990s to protest his denomination’s ban on same-sex marriage. He presided over a mass gay wedding event at UT. He ordained an elder who was an out lesbian.

Rigby watched 150 people leave the congregation, taking a large chunk of the church budget with them. He was hounded by Paul Rolf Jensen, a conservative Presbyterian lawyer who wanted Rigby defrocked. He faced a church tribunal for violating denominational rules.

Fear strengthened his resolve.

“There’s something about preaching from the gallows,” Rigby said.

In 2003, Jensen predicted that a church trial would cost Rigby his collar. “He’s going to tell the presbytery the truth,” Jensen told me, “and the truth will set him free to go to another denomination and a church that shares his beliefs.”

Rigby stood his ground: “Either they have to strip me of my ordination,” he said in a 2004 interview, “or the church has to change.”

The church did change. In 2011, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) voted to ordain openly gay ministers, elders and deacons (without requiring celibacy) and this year recognized same-sex marriage.

Rigby worries that LGBT Presbyterians emerging from seminaries may still encounter bigotry in the churches they serve. But he’s celebrating the progress of his denomination and his country.

On the Sunday after the Supreme Court ruling, Rigby decided it was time to put on his clerical robes again.

Boy, it’s been fascinating to read some of the Christian reactions to the Pew Research Center’s latest survey on American religion. The big takeaway, if you haven’t read the headlines, is that the Christian share of the population is declining while the number of religiously unaffiliated (atheist, agnostic or “northing in particular”) continues to rise. Which Christians are losing ground? Well, according to Pew, it’s the mainline Protestants (Methodists, Presbyterians, etc.) and Catholics. Evangelicals, apparently, are holding their own.

Here’s a sampling of responses to the survey:

- The church isn’t the problem, this Catholic blogger argues, divorce is! When families split up, children are less likely to attend church consistently or have a solid religious identity. These stats should not be seen as a victory for atheism, he writes.

- A Christian author claims Pew has a secularist agenda and skewed the results. It’s all part of a movement to attack Christianity. (This from an email his PR guy sent to media outlets today. Seems like a good angle for Bill O’Reilly.)

- Americans losing their religion? It’s Obama’s fault. Am I reading this Western Journalism piece correctly?

- On a more scholarly note, the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) contends that Pew played fast and loose with the Catholic population data as detailed here by researcher Mark Gray. (The Pew folks should address these concerns.)

No surprise there would be some grumbling among some Christians.

On the other hand, Christianity Today’s coverage of the report seemed rather gleeful given the good news (so to speak) for evangelicals, the magazine’s target audience. Check out the headlines: Pew: Evangelicals Stay Strong as Christianity Crumbles in America: Amid changing US religious landscape, Christians ‘decline sharply’ as unaffiliated rise. But born-again believers aren’t to blame.

Accompanying the article: a picture of an American flag with a cross where the stars should be.

Well, OK!

But enough about Christians. I need to spend some more time with the survey results to learn more about the religiously unaffiliated (often referred to as the “nones”). We’ve been talking about them — and their marked rise — for years. But it’s hard to get a handle on them. Who are these folks? They are not easy to pinpoint. Not all are secular. Not all are “spiritual but not religious.” Some grew up with religion; others didn’t. Their experiences and beliefs may vary wildly. If fewer and fewer people affiliate with a particular church or denomination, what will that look like down the road? What does it look like now? This is a goldmine for religion writers and other reporters who write about such trends.

Earlier this month, the Pew Research Center released a major global religion report, projecting growth and shifts among believers in the decades to come. I’ve yet to give it a thorough read, so I appreciated Tim King’s takeaway in Religion Dispatches. He explores the China factor and the often misunderstood term “unaffiliated.”

The big news — or at least the most eye-catching item — is that Muslims will likely overtake Christians in the next 50 years or so. That’s bound to freak some folks out. Of course, it may not play out this way. These projections come with a bunch of disclaimers. War, famine, the development of religion in China, etc., researchers acknowledge, might change things.

But this is a useful report in that it reminds us not to rely on our own narrow perceptions of the world. In past years, when I would assign my Journalism & Religion students to read Philip Jenkins’ terrific Atlantic article from 2002, the reaction was almost always the same. Most were shocked that Christianity was growing the fastest in the global south — particularly Africa. Most struggled with the notion that Christianity didn’t belong to the west.

The Pew report backs this up, noting that, by 2050, 4 out of every 10 Christians in the world will live in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s huge, though King points out:

However that number becomes a bit less impressive when you consider that sub-Saharan Africa’s general population is projected to grow at the rate of 131% and growth in the Muslim population of the region is projected at 170%.

So while the global Christian population is shifting south, the Christian share of the population of sub-Saharan Africa may actually decrease.

If Muslims eventually outnumber Christians, I wonder how this will change the Christian worldview/narrative for believers. I’m also curious how Hindu-Muslim relations will fare in the coming decades. The report predicts that India, though it will maintain a Hindu majority, is expected to become home to the world’s largest Muslim population (surpassing Indonesia). And then there’s the growth of Islam in the U.S. and Europe and the uncertain future of religion in China. People, there is just SO much, and it’s all fascinating.

If you don’t have time to read all 245 pages of the Pew report, read King’s piece. He picks six items and provides great analysis.

Campaign seeks to shed light on persecuted Baha’is

Iran makes the headlines every day. But in all those stories you’ve read in the newspaper or seen on TV, have you heard any mention of the country’s religious minority — the Baha’is? I’m guessing not.

On March 2, the Baha’i student group at UT organized a screening of Iranian-Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari‘s documentary “To Light a Candle,” which chronicles the persecution of Iranian Baha’is and their incredible resilience. The film shows how Iran’s Shia Muslim leaders deny Baha’is access to higher education unless they recant their faith. Instead, Baha’is risk their lives to attend their own underground university system, the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education. Students and teachers are regularly arrested, detained, and tortured. And the ripple effects are devastating, particularly when one considers the children whose parents are imprisoned.

The international campaign Education Is Not a Crime seeks to illuminate these human rights violations and pressure Iran to stop the persecution.

A campaign is sorely needed. It’s scandalous that we don’t know more about the plight of Iran’s 350,000 Baha’is who have suffered greatly since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. As much as Iran dominates the news (nuclear talks, funding of terrorists, etc.), we don’t see much coverage of these people’s lives.

My friend Khotan Shahbazi-Harmon moderated the panel discussion following the film screening at the Texas Student Union. She lost her father to the murderous regime not long after the revolution and said she is tired of having to call attention to the nightmare in her home country. How on earth is this still necessary 36 years later?

I wish I had the answer.

I wrote a column about the event. It’s published in Austin American-Statesman (behind a pay wall). I’m pasting the original, uncut version below.

I also highly recommend you see the documentary, which is both heartbreaking and hopeful. Check out the trailer.

Original column:

The news from Iran is troubling to say the least. Are the Obama administration’s nuclear negotiations misguided? Is Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu meddling in our affairs?

Hidden from the headlines and punditry of recent news cycles are the lives of ordinary Iranians. But their experiences demand our attention. On March 2, some 200 people gathered the University of Texas at Austin to illuminate the plight of Iran’s estimated 350,000 Baha’is who are denied, among other rights, access to higher education.

As part of the international campaign Education Is Not a Crime, members of the Austin Baha’i community and UT’s Baha’i student group organized a screening and discussion of “To Light a Candle,” a documentary made by Iranian-Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari.

The campaign has all the modern trappings— a slick website, celebrity endorsement, video messages and calls to tweet world leaders, including Iran’s Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. But the people I spoke to at the screening say they’re determined to go beyond hashtag activism. They believe Iran’s regime cares about world opinion, that with enough pressure, leaders will bend.

It’s hard to fathom that kind of hope.

“To Light a Candle” chronicles decades of merciless abuse of Baha’is — and their staggering resilience. When Spiritual Assembly leaders were rounded up and executed in the 1980s, they elected new leaders. When they were barred from the Iranian university system, they created their own, the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education (BIHE).

I attended the screening and served as a panelist for the discussion that followed. The content of the film wasn’t shocking to me. I had covered the Baha’i community as a reporter and heard the stories of imprisonment, torture and executions. And I teach about persecution of Baha’is in my Journalism & Religion class at UT.

But, as all good documentaries do, “To Light a Candle” provoked questions that suddenly felt fresh and urgent: Why does Baha’i suffering exist largely in the dark? Why do the mullahs find this religion so threatening? And why on earth would anyone stay in such a hostile place?

As religions go, the Baha’i faith, founded in mid-19th-century Iran by a prophet called Bahá’u’lláh, is relatively new and ostensibly innocuous. Baha’is believe in progressive revelation, the idea that God sent a series of divine messengers (Krishna, Jesus, Muhammad, etc.), each building upon the revelations of the earlier prophets. Followers eschew partisan politics, promote gender and racial equality and require the education of children.

But to the Shia Muslim establishment, the claim that God sent a prophet after Muhammad is anathema. Iranian clerics and government officials contend the Baha’i faith is not a religion at all but a political dissident group, an enemy to Iran and Islam.

The Iranian government bars Baha’is from higher education unless they renounce their beliefs (which the Baha’i faith forbids). The other option for young people is to go underground and, at great risk, earn a degree they may never be able to use publicly.

Thousands enroll in BIHE, taking courses online and in private homes. Many of the professors are themselves graduates of the institute. Some teach from other countries, including the U.S.

The instructors who attended the event in Austin spoke proudly of their students’ eagerness to learn. An audience member shared that after earning his bachelor’s degree from BIHE, he was able to pursue a master’s at UT.

But students and their teachers are considered criminals in Iran. They are regularly arrested, tortured and detained without official charges or legal representation.

Of all the Iranian government’s abuses Baha’is have described to me over the years, the denial of education seems to be the most disquieting.

Their commitment to scholarship is not a secular ideal but a religious one. In the Baha’i faith, universal education is compulsory. The prophet Bahá’u’lláh said: “Regard man as a mine rich in gems of inestimable value. Education can, alone, cause it to reveal its treasures, and enable mankind to benefit therefrom.”

Time after time in the documentary, we learned of Baha’is who had the opportunity to flee their home country but chose to stay and continue to study and teach with BIHE. They felt an obligation to “help Iranian society.”

A particularly heartbreaking case is the Rahimian family. In the 1980s, teenagers Kayvan and Kamran Rahimian saw their father Rahim sent to prison, tortured (his tormentors were particularly fond of flogging the soles of his feet) and later executed. Now fathers themselves, Kayvan and Kamran share a prison cell because of their teaching. Kayvan’s wife died of cancer a few years ago. Kamran’s wife, also an educator, is serving her own sentence. The children are growing up without parents.

During the panel discussion after the screening, the moderator Khotan Shahbazi-Harmon, whose own father was executed after the Islamic Revolution, asked for my gut reaction to the film.

I answered bluntly: “I don’t understand why they stayed. No country is worth that. No faith is worth that.”

It seemed unfair that the Baha’i faith, which has been under siege since its inception, could have a rule against recanting — even to save one’s life.

Bijan Masumian, a wise and soft-spoken Austin researcher, explained that Baha’is are connected to the people who came before them and to those who will follow. The rule reminds them that they are called to think outside their own circle, their own family, and to consider the whole of humanity.

He added: “You cannot eradicate a religious belief system by persecution. The harder you push, the more resilient they become.”

At the end of the Q&A section, a man with a white mustache raised his hand. “I know of a way we can help,” he said quietly. “Light a candle, no matter how big or how small. There is no darkness — only the absence of light.”

One of the panelists leaned over to me and whispered, “That’s Baha’i theology 101.”

I will be co-moderating an interfaith panel (Jewish, Buddhist, Christian and Muslim leaders) on Thursday, Feb. 19, at Huston-Tillotson University. If you are in the Austin area, PLEASE COME. Here’s the info.

In the meantime, here are some reflections on the value and challenges of interfaith conversations over the last dozen or so years (from my perspective as a religion reporter). I’ll circle back to the upcoming event. Here goes: In terms of learning the religion beat, I cut my teeth on interfaith dialogue. It was early 2002 as our country was still trying to make sense of 9/11 and faith leaders sought to create a safe space where everyone could learn about Islam from the Muslim neighbors who had until then not drawn much attention. There was an air of urgency, a sense that this work was imperative if we were going to move forward without being hopelessly fractured. There were so many events back then. Panel discussions and pulpit swaps and invitations to churches and mosques and synagogues. All of these alliances. Some of them already established. But many of them, particularly with the Muslim community, delicate and new. (Sheikh Safdar Razi, still new to the U.S. and struggling with English, emerged from his small Shiite community on Sept. 12 to speak at the Texas Capitol. “Somebody has to go out and tell them we’re not terrorists,” he told me later.)

In the meantime, here are some reflections on the value and challenges of interfaith conversations over the last dozen or so years (from my perspective as a religion reporter). I’ll circle back to the upcoming event. Here goes: In terms of learning the religion beat, I cut my teeth on interfaith dialogue. It was early 2002 as our country was still trying to make sense of 9/11 and faith leaders sought to create a safe space where everyone could learn about Islam from the Muslim neighbors who had until then not drawn much attention. There was an air of urgency, a sense that this work was imperative if we were going to move forward without being hopelessly fractured. There were so many events back then. Panel discussions and pulpit swaps and invitations to churches and mosques and synagogues. All of these alliances. Some of them already established. But many of them, particularly with the Muslim community, delicate and new. (Sheikh Safdar Razi, still new to the U.S. and struggling with English, emerged from his small Shiite community on Sept. 12 to speak at the Texas Capitol. “Somebody has to go out and tell them we’re not terrorists,” he told me later.)

Austin Area Interreligious Ministries (now known as iAct) took the lead in pulling people together — Christians, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, Baha’is, Hindus and others. The objective was finding common ground, highlighting the heartwarming aspects of the varied religions, particularly Islam, which President Bush had asserted on the evening of Sept. 11 was a religion of peace. Not everyone went along with this. For one thing, some Christians, especially more conservative evangelical Christians, found it unacceptable to engage in a discussion with non-Christians without being able to witness. I remember one African-American minister unleashing his frustration at an interfaith event. His religion called him to spread the Gospel, he said, not pretend that all religions were equally valid.

As time went on, another challenge revealed itself: The troubling passages in holy texts. The very source for many religious extremists to commit violent acts. Could they be ignored? People tried. Then, one day, Rabbi Kerry Baker had enough. At roundtable discussion with Muslim journalists from overseas, after people made comments about terrorists misinterpreting the Quran and not representing “true Islam,” Baker banged the table with his hand and demanded that believers own up to their problematic scriptures and stop pretending that their religion didn’t inspire violence. The visiting journalists seemed a bit stunned.

(Incidentally, Baker, who once said it’s his “lot in life to say unpopular things,” was including his own tradition in this comment.)

The point is, no, it wasn’t perfect, but I don’t know where we would be without these conversations and events that took place after 9/11. Even if religions were sugarcoated and people often avoided tough questions, at least we learned a little about each other. At least we saw the humanity in each other. (And, for the record, sometimes people did push the boundaries, did ask the tough questions, etc.)

I don’t know where we are today with regard to interfaith dialogue. Now that I’m no longer a religion reporter, it’s harder for me to assess. I do know that some evangelical Christians have found a way to promote understanding about world religions in a way that doesn’t compromise their beliefs. Pastor Tom Goodman of Hillcrest Baptist Church did a terrific series of live interviews at his church a number of years ago. (I wrote column about it.)

I also recently learned about a conservative Christian named Jim Miller whose Church Without Walls promotes dialogue between Muslims and Christians. People don’t have to agree. But they have to live together.

The Chapel Hill murders, the arson attack on the Houston mosque and other anti-Muslim acts here in the U.S. should remind us that there is still work to be done. (Let’s face it, there will always be work to be done. There will always be hatred and bigotry and violence.)

And I think that, generally, we seem to be catching on to the importance of religious literacy. At least I hope we are. But it’s tricky in this age of information overload. We have gone from being simply ignorant (not having much information about other religions) to actively misinformed (having access to too much and often erroneous information). Thanks, Internet.

That’s why this conversation at Huston-Tilloton is important. We need to be sure that we’re going out of our way to bridge gaps and draw more people into the dialogue. I think we have moved on from the notion that all religions are different paths up the same mountain. We want something more honest and challenging now — even if it’s just to listen to a group of people give their take on some key questions: Why am I here? Where am I going? What helps me get there? What are obstacles to this path? It will, of course, be more than just answering those questions.

What I love about this panel is that we have a Southern Baptist minister and a Sunni Muslim imam and a Reform rabbi and an ordained Buddhist monk who is also a psychologist. They will each speak from the heart about what their tradition teaches and what it means to them. Some of their beliefs may overlap, but many won’t. These are very distinct paths, and it’s important for us to see where they diverge, not just where they intersect. Remember, we don’t have to agree. But we do have to live together.

I’m thinking a lot these days about James Foley. He felt a calling, they say, to tell the stories of people who might not otherwise be heard. That is what makes a great journalist. It’s part of it anyway. He also clearly had courage, the kind I cannot imagine having. The kind that draws you into danger and mayhem and uncertainty. The kind that makes you vulnerable to kidnapping and — even when you are kidnapped and eventually released —allows you to return. To keep doing your job. Your calling.

I’ve never been THAT kind of journalist. No story was so important that I would put myself at such risk. The way Foley did. The way Danny Pearl did.

Both admirable journalists. Both murdered by vicious thugs and in a manner you can’t even bring yourself to imagine.

So I’m thinking about both Foley and Pearl. And specifically about faith and religious identity. Foley, by all accounts, a believing Catholic. Pearl, a non-religious Jew who was forced to declare his Jewishness before the execution.

I imagine that prayer and belief brought Foley some measure of comfort during his captivity. In a 2011 letter to his alma mater, he wrote about faith sustained him during a previous imprisonment in Libya. And it was interesting to read what his parents have said in the days following his death. How he was a gift from God, that he drew his strength from God. The family even received a phone call from Pope Francis during which the pontiff praised Foley’s mother for her faith. And then there’s the question of forgiveness. It seems crass for a reporter to ask this so soon after their son’s death and on the very day the Foleys watched the video of the beheading, but a reporter did ask if they could forgive the killers, according to this story in the Daily News.

John Foley’s response:

“Not today,” he choked out as his voice trailed off. “As a Christian, we have to …”

I wonder how the family will grapple with the Christian concept of forgiveness in the years to come. And again, I’m brought back to Danny Pearl and his heartbroken father, Judea Pearl. I was the reporter who asked the forgiveness question, albeit seven years after Danny’s death. I looked up the column to remind myself exactly how Judea answered.

A few minutes into our conversation about how efforts to make peace between Jews and Muslims help honor his slain son, Judea Pearl stopped me in my tracks by announcing that he believed God owed him a personal apology. Let me back up. I had called Pearl, father of murdered Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, to discuss Sunday’s Abraham Walk at the Dell Jewish Community Campus. Pearl will speak at the annual interfaith event that brings together Jews, Christians and Muslims to retrace the journey made by their common ancestor, Abraham.

Our phone interview came hours before the sunset ushered in Yom Kippur, when Jews around the world gathered in synagogues to stand before God and atone for their sins. A local Jewish scholar had suggested I raise the question of how Pearl deals with his son’s murder by a militant Muslim group in Pakistan almost seven years ago when Daniel Pearl was on assignment there. What better time than Yom Kippur to talk about forgiveness?

Pearl’s answer was swift and raw.”I am Jewish. I don’t buy the Christian notion of forgiveness. I don’t think there’s any inherent mystical power in the act of forgiving. You forgive when the person who did a certain crime acknowledges regret and change of behavior. Until that happens, in the Jewish tradition, forgiveness doesn’t catch.”

Then Pearl said evenly, “God owes me a personal apology, not only to me but to all decent people in the world for betraying their expectation of what good and evil is in this world.”

This sentiment will always stay with me. How can you forgive someone who has not atoned? And why would you? And this idea of a loving God who supposedly gives you strength in your final hours? Judea Pearl had a bone to pick with that God for letting everyone down. I am glad he was so honest, so unflinching. But as someone who grew up Catholic, I also understand why the Foleys might find relief in forgiveness … one day.

I’ll be thinking about these good men — Foley and Pearl — for a long time. I am not thinking of the murderers and their vile interpretation of religion. As John Foley said so succinctly, “Not today.”

Meet Dr. David Zuniga, Zen priest and psychologist. Isn’t this a terrific photo? He really does laugh a lot. This captures him well.

Meet Dr. David Zuniga, Zen priest and psychologist. Isn’t this a terrific photo? He really does laugh a lot. This captures him well.

I first wrote about David in 2006 after he became the first Westerner ordained in the Taego lineage of Korean Zen. (A grueling ordination process that you can read about here.) We stayed in touch over the years as we started families (he and his wife have two delightful daughters) and reconnected this summer to talk about his psychotherapy career and the ways in which therapists incorporate Buddhism into their practice. Fascinating stuff. Of course, we wound up talking about kids and the challenges of teaching them about Zen, which we’d also explored a few years ago in an Austin American-Statesman column.

A short bio on David, then the Q&A:

Zuniga earned his Ph.D. in clinical psychology and is now a post-doctoral fellow with a therapy practice in Austin. (Check out his professional website, which features a blog with great info on mindfulness.) He received a master’s degree in comparative religion from Harvard Divinity School, was one of the first Buddhists to be certified as a professional hospital/hospice chaplain and worked for over a decade as a Zen/interfaith chaplain in pediatric and adult end-of-life healthcare. In addition to his counseling practice, he is finishing a book on Zen, mindfulness and end-of-life care for Wisdom Publications. Find him on Facebook and on Twitter @drdavidz.

How would you describe mindfulness to someone unfamiliar with the term?

Great question! Part of the way I would describe mindfulness to someone depends on the unique interests, background, and situations that they are dealing with in the moment. It’s always important to speak in a language that can be understood.

Mindfulness, as a system of meditation and philosophy, arose over 2,000 years ago from within ancient Buddhism. More recently, it has come to be integrated into some of the leading clinical approaches in mental healthcare including mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). In fact, many theorists and researchers now argue that mindfulness is the leading paradigm in mental health. Mindfulness, and mindfulness-related practices, are also widely and successfully utilized in biological healthcare.

Because I utilize mindfulness in both psychology and in a Zen context, I’ll try to define it in a way that draws upon both of these methodologies. Mindfulness is a system of present-moment meditative attention and engagement brought to bear on all activities of existence including, but not limited to, activities of daily living (e.g., walking, sitting), interpersonal processes (e.g., talking, listening), behavioral patterns and activities (e.g., eating, cooking), emotions (e.g. fear, anger, sadness, joy), cognitions (e.g., automatic thoughts, attitudes) and biological processes (e.g., breathing, heart rate variability, muscle tension, perspiration). This method is active yet non-judgmental; it observes all phenomena through their inevitable processes of change. One of the ways mindfulness was first used in healthcare was for treating intractable, chronic pain. Similarly, I’ve used mindfulness meditation and philosophy in healthcare settings with pediatric and adult oncology and hospice patients. And I’ve seen mindfulness help people from a wide array of backgrounds deal with some of the most profound challenges in the human condition (e.g. trauma, depression, grief, divorce etc.).

Researchers in mental health have generated a wealth of empirical data attesting to the power of mindfulness to alleviate an array of challenges and clinical concerns. Buddhists will often say that mindfulness is a profound way, but not the only way, to transform suffering and cultivate gratitude, wisdom, and compassion. This dialogue about mindfulness between Buddhism and psychology is exciting and fruitful.

We have talked about mindfulness in psychotherapy and some of the debate around incorporating Buddhist themes. Some say it’s perfectly congruent with Buddhism; some argue mindfulness is congruent with other/all religions; some don’t seem to acknowledge the Buddhist connection at all. As a Buddhist and a psychologist, how would you like to see this handled?

This is an important question, and part of the way I could answer this question depends on what type of therapy and what type of Buddhism is being discussed. I think that’s an important point because people tend to assume that therapy is basically the same, and similarly that all forms of Buddhism are largely the same. But there are hundreds of different, recognized forms of therapy, and there are thousands of different schools of Buddhism.

William James speculated that Buddhism represented the future of psychology. And theorists since the origins of psychology and psychiatry (e.g. Carl Jung) have sought to interpret Buddhism and utilize some of its methods for clinical work. Buddhism, and its related forms of meditation, have often been conceptualized by mental health theorists via whatever is the dominant paradigm of psychology in the particular era. For example, in the early days of psychology, Freudian-derived approaches were dominant, so Buddhism and Buddhist-practices (e.g. Buddhist forms of meditation) were conceptualized through a psychodynamic (Freudian-based) lens. Now cognitive and behavioral approaches are the most popular clinical interventions. And similarly, mindfulness is re-conceptualized in mental health as a cognitive-behavioral technique.

According to the original Pali (a dialect of Sanskrit) Buddhist texts, which first articulated the practice of mindfulness, the Historical Buddha was initially terrified of the fact that he would someday grow old, grow sick, and die. In psychology aging, sickness, and death are often referred to as the “existential givens” of human existence. From a Buddhist perspective, the practice of mindfulness is grounded in transforming the fear of death that most people feel. For example, the main Buddhist text which describes mindfulness is the Mahāsatipatthāna Sutta. In the Mahāsatipatthāna Sutta mindfulness is consistently explicated as meditating directly on the inevitability of death. The Buddha wasn’t trying to be negative or pessimistic. The Buddha observed that by facing these existential inevitabilities skillfully they could be transformed, and people could be free of suffering and live more authentically and compassionately. Yet these existential and humanistic dimensions of mindfulness, which are so central to a complete practice of mindfulness, are less often discussed in contemporary psychological explications of mindfulness. Humanistic (e.g. Carl Rogers, David Cain) and existential approaches (e.g. Irvin Yalom, Kirk Schneider) are also main schools of thought in psychology. Exploring the humanistic and existential roots of mindfulness in relation to psychology represent a largely untapped resource in Western-based mental health.

The question of commonality between mindfulness and other religious traditions and their practices is an interesting and important one. In the original texts which first proposed and articulated the practice of mindfulness, the Buddha consistently described mindfulness as a direct way to overcome the fear of death, transform related existential concerns, and overcome a false sense of isolation that often causes suffering.

The Buddha, particularly in the Pali Canon (oldest preserved collection of Buddhist texts) taught mindfulness as a way to experientially realize a state of no-self (Pali, anatta). No-self is one of the central teachings of Buddhism and observes that all sentient life forms lack a separate, unchanging, autonomous self. As everything changes, human existence can be prone to suffering. Mindfulness meditation was formulated to cultivate compassion and alleviate the forms of suffering that frequently occur in response to the evanescent nature of existence such as aging, sickness, and death. In the Buddha’s time, the term atta essentially was used to refer to what we now call a “soul” (and this notion of anatta is why some Buddhists identify with atheism or agnosticism). So by offering a philosophy grounded in the idea of anatta, or no-soul/no-self, the Buddha was arguing in a powerful way for a literal interconnection between all things.

The Buddha wasn’t a nihilist. We exist. And our existence operates in concert with everything in existence; this is the joyful interconnection of all beings. Manifestations of existence change, they are always in a state of flux. This is why Buddhists often say “nothing is born and nothing dies.” It’s a provocative intellectual idea, and it is more than just a philosophical idea. If we can feel this deeply, on a heart level, in a lived, embodied way, we can live in harmony and union with the symphony of existence. The Buddha suggested that as one cultivates mindfulness, he or she gains direct insight into the constant flow of change in and around us. As we cultivate equanimity with change, we overcome suffering. How similar or different this philosophy and practice of mindfulness is to other religions can be debated.

As a Zen priest, what principles guide you? Are there certain core beliefs and practices essential to your identity as a Buddhist?

There are many different kinds of Buddhism throughout Asia. It can be argued that Buddhism has undergone change when coming to Western countries. Zen is one type of Buddhism. While there are different kinds of Zen, generally Zen defines itself as a tradition operating outside of words, language, and concepts. Most forms of Buddhism would agree with that same definition, but Zen often cultivates a radical adherence to present moment, direct experiencing. Zen could be understood as a mystical tradition within a wider (Buddhist) mystical tradition.

Beliefs are important, and beliefs help to shape our experience of reality. As a Zen Buddhist, I believe that our practice is even more important than any beliefs we have. Mindfulness is one of my main personal forms of practice, but not my only form of practice. I utilize different practices based on what I need in the moment. The guiding principle of my life is to become an ever more skillful healer in the world, so I can help transform suffering and cultivate compassion and joy—in my own life and in the lives of others. In my personal Zen practice, I utilize mindfulness and other forms of meditation to cultivate an experiential reality of no-self. In other words, I practice so I can experientially realize the reality of interconnection that exists between all beings and things. We are all interconnected. Transforming the illusion of a seemingly dichotomous existence liberates one from suffering.

Like me, you’re a parent of two wonderful little girls, and we’ve discussed the challenges of introducing kids to Buddhism when there aren’t many (if any) family-friendly sanghas in Austin. While that community connection may be lacking, I’m wondering about practicing some kind of ritual in the home. Is this important for children? Do you use any Zen (or other) rituals in your home?

I love this question, though it might be confusing to some folks because, as you point out, I’m a fully ordained Zen priest and have two children. Most forms of Buddhism require their ordained clergy (monks/priests) to be celibate (e.g. like Roman Catholicism). My lineage of Zen allows their ordained clergy to marry (e.g. like Protestant Christianity). So I’m a fully ordained Zen priest and married with two children, which is great because I believe my Zen practice informs my family life, and my family life makes me a better Zen priest. All things are interconnected.

All religions have their strengths and growing edges. Zen is very strong in the domains of meditation and philosophy. The Buddha taught that the sangha (the community) is the most important dimension of the spiritual path. And yet Zen in the west has room to improve in terms of being family-friendly. One of my dreams for Zen in the west is for Zen/Buddhism to become more accessible to families as a whole. This is not to proselytize. You give with an open hand, with no attachments. I know a lot of people who would like to practice Zen and yet don’t experience Zen groups as being family-friendly. Not surprisingly, many parents who are interested in Zen don’t know how to share the tradition with their children.

For me, it’s been really easy to share Zen with my kids. But I’m a Zen priest! My first step is to be the best Zen practitioner I can be. I’m not perfect, obviously. But I try to take honest inventories of myself so I can be as compassionate and mindful as possible, which certainly helps with being a parent. I share Buddhism with my kids. We celebrate Buddhist holidays like Vesak and Bodhi Day, and we also do some other rituals and holidays like Day of the Dead. We read Buddhist-based books, I meditate with my kids, I chant with them. I share Buddhist principles with them; for example, we do mindful eating or talk about being fully present when we color or play with one of our pets. Sharing your Buddhism with your kids is basically sharing your life with your kids. Mostly my wife and I try to cultivate a culture of joy in our house. And I also don’t expect my kids to be Buddhist. They choose their own path. I don’t expect them to be just like me. I encourage them to be fully who they are. And I love being surprised by the unfolding and manifestation of their own unique paths. I share Zen with them, but my wife and I also discuss other religions and systems of philosophy with them too.

Being a parent is perhaps the most direct practice of no-self in my life. Parenting teaches me, on a daily basis, to step outside of the small, limited desires of a sense of self. My children’s happiness is more important than my own sense of happiness. My children and my wife are my teachers, and they are the best Zen practice I have.

Q&A: Dodson talks doubt … and faith in Jesus

The mission of City Life Church exists to renew cities socially, spiritually, and culturally with the gospel of Jesus. Like the early Christians, we believe that our presence in the city should enhance not drain urban resources. We see social, spiritual, and cultural brokenness in the city, and in our lives, and are committed to an enlivening power for the whole person and city, which comes from outside of ourselves, in Christ.

We gather on Sundays, downtown, in Ballet Austin next to Austin Music Hall and though out the city in homes, pubs, and parks during the week. We have a lot of kids, young adults, and families with a few older families sprinkled in (we’d love more). We are a church that reflects the creative ethos of our city—entrepreneurs, artists, students, DIYers, and so on.

Our beliefs center around Jesus as Christ and Lord. He is a forgiving Redeemer and a benevolent King. His authority gives us a north star for living, as opposed to subjective personal beliefs, and his loving grace nurtures deep spiritual satisfaction we can’t find anywhere else. His gospel is the good and true story that Jesus conquered sin, death, and evil through embracing the brokenness, injustice, and sin on the cross, and through his resurrection is making a whole new world. All other doctrines are secondary to our belief in him. We do not believe we are superior to any person or faith, but we do believe in the supremacy of Jesus.

Our mission is adapted from Jesus, whom we see in the Gospels reversing the order of things—the proud are humbled, the marginalized are brought into the center, the diseased are healed, the deranged are given sanity, and sinners are forgiven. We are trying to follow in his footsteps, but we’re also aware of our own weakness, which is why we return to his forgiving grace for our own pride, love of comfort, tendency to just take from the city.

Since we believe the church should be display of God’s grace to the city, we put the mission in the hands of our people. This happens through our 4 neighborhood churches, who together work socially in three low-income apartments in our city to love and mentor kids, teach them the life-changing message of Jesus, and provide nutritious meals. This is carried out in partnership with Hope Street and are also deeply committed to Austin Children’s Shelter. Since the Heavenly Father loves the orphan, we believe he has sent us to bring his message of acceptance, forgiveness, and healing though Jesus.

We also believe that Christians should be exemplary neighbors and citizens culturally. So we teach, train, and encourage people to add value to the city through their work. We have quite a few entrepreneurs who have created a number of businesses in Austin, leading to job creation and cultural flourishing. Our musicians have been engaged in making great culture, starting Music for the City.

Your new book Raised? invites skepticism as a gateway to belief in the resurrection. This is an interesting approach — acknowledging how unbelievable the claim is that Jesus died and rose from the dead. How did the book come about and what makes your approach unique?

Spending significant time in three creative class cities (Minneapolis, Boston, Austin), I’ve tried to listen to people’s concerns and objections to Christianity. A lot of people have really good questions and doubts about the Christian faith. When I step back and look at just our core beliefs, it’s pretty audacious to claim that God became a baby, died such a unique death that it absorbed the evil and sin of the world, and that he came back to life after three days in a cold, dark tomb. In a scientific age, that’s really hard to swallow. We just don’t see people come back from the funeral home. I don’t blame people for doubting it. Christians should doubt their faith more and skeptics should press into their doubts to discover deeper reasons for faith or unfaith.

If you doubt the resurrection, you’re in good company. The disciples, Jews, Greeks, and Romans of Jesus time all did too. If you came to a Greek in the 1st century and told them Jesus rose from the dead, they’d scratch their head and say, why would he want to do that? The body is contaminated, a cage, and dying is our freedom. Different Greeks had different spins on this, but essentially no Greek person would find resurrection desirable. Jews also would scratch their heads since they believed in one big resurrection of everyone at the end of time to face judgement. So one person, in the middle of history, didn’t fit with their age-old their theology. But Jews and Greeks changed their beliefs about resurrection instantly. They turned on a dime, changing centuries-held beliefs overnight. What would provoke philosophical Greeks, and staunch Jews, to change their mind in an incredibly short amount of time? The only plausible explanation is that they encountered a risen Jesus or heard the news from someone that did. Why else risk the scorn, ridicule, mental and spiritual instability, of switching you beliefs just like that?

So I say doubt it but doubt it well. Let’s not assume the arrogance of our cultural scientific moment and rule out the supernatural. Lets be more open-minded, do good history, and then consider the difference such a teaching has. It is worth risking the scorn? I believe so.

In our email exchange, you used the term centrist to describe your views. I’m so accustomed to hearing that word in a political context. What does it mean in the Christian world?

Briefly, we try to avoid liberal and conservative camps in our theology and politics and center our views on Christ. Conservative views often add to Christ teachings, saying we have to clean up, be more moral to be accepted by Jesus. Liberal views tend to subtract from Christ’s teachings, denying his clear claims to be God, to have died for the world, risen from the dead. We don’t what to add or subtract from the Jesus we see in the Bible and have met through profound personal encounter. We prefer to be centered on him, and not use Christianity of Jesus for strong political agendas. Jesus’ agenda of grace cuts right through the camps.

He confronts us in our bentness away from him (left or right, self-righteous or unrighteous), and says very clearly—“You need me. You need forgiveness for trying to add or subtract from me. And I’ll forgive you and give you a life better you can make for yourself. But you have to give up on yourself and give into me, where you will find perfect acceptance and love, enduring hope and joy.”

As these interviews are geared toward improving our religious literacy, I like to ask folks about misconceptions. Is there anything about your particular theology or church that you think is misunderstood?

I think I’ve addressed a few of those already. I do believe in what you are doing, Eileen, that we should all become more religiously literate. Let’s talk more about the deep things of life and culture with one another, respectfully, truthfully, and winsomely. And let’s work together of the renewal of our city. Let’s understand, not just blindly accept, the wonderful weirdness of Austin.

If you don’t already know him, let me introduce you to Harish N. Kotecha, a Hindu community leader here in Central Texas. He’s agreed to be my guinea pig in my effort to improve religious literacy through short Q&As with people of different belief systems. These will be small snapshots into world religions (and atheism) with the hope that we might learn something new, correct a misconception or two and even be inspired to pursue more knowledge on our own.

It made sense to me to start with the oldest religion — Hinduism — and to call on one of the nicest and hardest working faith leaders in the Austin area. A bit about Harish: He was born in Uganda and lived there until dictator Idi Amin abruptly expelled the country’s Asian population in 1972. Harish and his wife Shobhna fled to the U.S. where Harish worked for IBM as an engineer/manager. Now retired, he’s devoted himself to community, helping to develop Hindu temples and leading/participating in various civic and cultural organizations. He energized the Hindu community in Austin to help with the resettlement of Bhutanese refugees in recent years and remains committed to resettlement efforts. In 2010, he founded Hindu Charities for America “with the vision of motivating the Indian communities across U.S. to help with education of homeless and other economically disadvantaged children.” As Harish sees it, this country has given him a home and prosperity, and he wants to give back. Harish and Shobhna have a daughter, Sonia, who works for CASA in Travis county, and son, Savan, a successful songwriter.

Here is our interview:

You are very active in getting the word out about the Hindu community in Central Texas through your charitable and interfaith work. What should we know about your faith community?

By and large, the Hindu community of 15,000 to 20,000 in Austin is mostly educated, economically well off and fairly traditional. There are six large places of worship and various cultural and civic organizations that are helping keeping the culture alive. It is said that UT at Austin typically had three to four thousand Hindu students while the Indians in Austin are doctors, lawyers, engineers, IT experts, entrepreneurs, and employed in companies in a professional capacity. The culture and traditions are deep rooted and the ties with India are strong for many. There is a focus on education of the children.

A friend of mine recently dedicated herself to Sanatana Dharma under the teacher Sri Acharyaji. We’ve been talking about her spiritual practice quite a bit lately, and it’s got me wondering about labels. She doesn’t call herself a Hindu or refer to her belief system as Hinduism given the non-Vedic origin of these terms. How do you feel about these labels?

As I understand it, Sanatham Dharma or “the eternal truth” is the oldest religion and not founded by one person. There are four Vedas, the Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda and Atharva Veda. The Vedas are the primary texts of Hinduism. They also had a vast influence on Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism. Traditionally the text of the Vedas was coeval with the universe. Scholars have determined that the Rig Veda, the oldest of the four Vedas, was composed about 1500 B.C., and codified about 600 B.C. It is unknown when it was finally committed to writing, but this probably was at some point after 300 B.C.

Just as have we have teachers or trainers to acquire various skills, in Indian culture, to learn and practice religion, religious teachers (Gurus, Swamis, etc.) are common. People follow the one they feel comfortable with. Fundamentally, we all understand truth is one, but there are many paths to learn truth and there are many names give to the same truth. God is one; there are many ways to realize God. For example, Harish is one, but people know him as husband, father, employee, friend, social worker, etc., depending on the role he plays on the screen of life. Similarly there are different forms of the one and same God.

Given the multiplicity of religious teachers and religious practices, labels develop – it is human nature. Better understanding is reached from teaching of writings of those understand. Sri Pravartak Acharyaji’s teaching appears to evolve from Vedas and Hinduism. Many will say that Hinduism is a way of life, not a religion. There was an interesting article in Newsweek by Lisa Miller that is titled: We are all Hindus – Hinduism, as some maintain, is a way of life.

Hinduism is the most challenging (in a good way!) religion I’ve studied. It is ancient and complex with such a wide range of beliefs and practices. I think Westerners have a lot of misconceptions about the religion. I’m sure you have a long list to choose from, but can you give me just a few examples of what people in the West get wrong about Hinduism?

This is an interesting question. Over past several years some reporters have asked this question. The most common misunderstandings I have come across are:

- Hinduism is a Polytheistic religion – meaning there is a belief in many Gods. This is untrue – Hindus believe there is one God, but there are many paths to realize God. It is the only religion in the world in which a person is given the freedom to choose to relate to God in the way that suits them best, whatever that may be.

- Hinduism has thousands of Gods: Hindu scriptures state that there are many divine/spiritual beings in the universe – It has been interpreted to mean that there are many Gods. This was most likely never intended to be taken literally, as the Hindu scriptures are full of symbolic metaphor and esoteric meaning.

- Hinduism supports the caste system: Caste system came about not though Hinduism but by people who looked down on others. It unfortunately became part of Indian culture and got related to religion.

Along those lines, what is the most challenging aspect of being part of a minority religion here in Texas?

The most disturbing thing from my experience has been conversion of Bhutanese Hindu refugees to Christianity. These folks came in as refugees to a country totally alien to them. They are innocent, not knowing what they are getting into. With offer of material benefits, jobs, availability of services, many have been coerced to convert to Christianity. Not in Central Texas, but in some other parts of the country, a few of those who were converted committed suicide. Another incident is where a Hindu inmate was baptized in a correctional facility! There was no reaching out to temples or Hindu community by the Prison Ministry. We have since then registered a couple of temples to the Prison Ministry.

Hindus and Jews do not proselytize. So such incidents, while such practices are common in many parts of India, are disturbing to experience in Central Texas.

The religion beat’s disappearing act

Veteran religion reporter Julia Duin posted a state of the God beat on Get Religion. It’s illuminating. And depressing. But I can’t say it’s surprising. When the Religion Newswriters Association held its annual conference in Austin this past fall, it seemed that every other person I talked to was a former staffer at one newspaper or another. Many were freelancing, which is a hard way to make a living.

Julia provides some grim anecdotes about the disappearance of the religion beat in newspapers across the country. I’m sad to see the beat fade at my local paper, the Austin American-Statesman. But in this day and age, specialty beats are an endangered species. As an advocate of religious literacy, I see the lack of a dedicated religion beat — and, for that matter, the lack of dedicated newspaper readers — as a real problem. Good religion writers educate us not only about people with different beliefs from our own. They also shed light on our own beliefs, our own tribe, so to speak. Again, you need readers to be effective. The bright spot in Julia’s GR post is what’s happening with Religion News Service, which has assembled a freelance team of some of the best faith reporters in the country.

But — there’s always a but — I do take issue with one of Julia’s observations on coverage of atheism and secularism. She writes:

… [S]pecialists have had to get current with the fast-growing ranks of the “nones,” which, according to the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, are an estimated 19.6 percent of the American population. Their numbers have ballooned in recent years, as have the numbers of outspoken atheists, creating an interesting conundrum for religion-news specialists because coverage of the non- or anti-religious gets tossed in the lap of the religion reporter. On one level that’s logical, but, still, stop and think about that for a minute. How many stories do sports writers produce about people who hate sports? Do fashion writers cover those who hate fashion?

This comparison doesn’t work. Atheists are actively engaged in the discussion about the role of religion in public life. Many of the “nones” are searching for meaning and rituals and are crafting their own set of beliefs and traditions for their families. Heck, we even have atheist churches now. And on top of all that, Christian leaders are constantly talking about reaching the “unchurched.” They are constantly lamenting secularism in this country. Believers and skeptics go hand in hand when it comes to comprehensive religion reporting.

Otherwise, this is a post worth reading and reflecting on. Where are you getting your religion news these days?